Rebetiko by Christoforos Marinos

‘In order to get access to the past,

one first has to deal with the present,

to make his way through the present and what is at stake in it’

Hubert Damisch

Rebetiko is arguably a thing of the past – but if so, then why revisit it?

Georges Didi-Huberman offers a succinct answer in ‘Coming Out of Time,’ an essay in the form of a letter addressed to Maria Kourkouta, director of the film Return to Aiolou Street (2013): ‘To be able to get out of past times, though, we must know how to return – at any time – to the immanence of their work, their returns, revivals. Hymn is not dead. It may survive where we least expect it – in a rebetiko folk poem, or an experimental short film.’

Indeed, hymn is not dead. And rebetiko itself lives on, disproving Dionysis Savvopoulos’s well-known lyrics from his album To Perivoli tou Trelou (1969): Σα ρεμπέτικο παλιό σβήνει η φωνή μου και σκορπάει [My voice fades and scatters like an old rebetiko].

It’s true, hymn survives in rebetiko music, especially of the pre-WW2 period. Listening to Smyrneiko Minore (1919), a gripping performance by Marika Papaghika, we imagine a time ‘released’, we are transported out of time. In this sorrowful, slow-burning love song in the amane style, Papaghika takes as long as three and a half minutes to convey her heartache – in a few short words:

Αχ, αν μ’ αγαπά κι είν’ όνειρο ποτέ ας μη ξυπνήσω. Ποτέ ας μη ξυπνήσω / με τη γλυκιά σου χαραυγή, Θεέ μου, ας ξεψυχήσω.

[If it’s a dream, that I am loved, may I never wake / May I never wake / When your sweet dawn comes, my Lord / Let me fade away]

These dense, poetic lyrics, encapsulating so many powerful concepts and images, are a characteristic example of the emotional power of rebetiko.

According to Yorgos Tzirtzilakis, in his essay Sub-modernity and the Labor of Joy-Making Mourning, words typically used to translate Homeric πένθος – mourning, grief, heartbreak, sorrow – are characteristic of rebetiko songs. Even though ‘rebetika defy translation,’ as Jacques Lacarrière aptly observes in his Dictionnaire amoureux de la Grèce [Dictionary of the Lover of Greece], ‘when they speak to prison, love, loneliness, exile, jealousy, betrayal, migration, they become universal.

Anestis Ioannou, Ιn Your Shoes, On Rooted Seeds,2021, acrylics, textile and collage on bleached denim,150×200 cm

Giorgos Kontis, Rebetiko, 2021, installation, mixed media, 215x220x160 cm

Nikos Papadopoulos, Votanikos’ Bloke, 2021, metal threads on black aluminum sheet, 33,1×60 cm

The thematic exhibition Rebetiko is all about love, escape, ‘joyful mourning,’ and all the thoughts, memories, and symbols associated with this ‘major occurrence in modern Greek culture,’ as the composer Nikos Mamangakis has fittingly described it. Rebetiko is a contemporary art exhibition of universal appeal, to the extent that the subject it surveys appeals both to Greeks and lovers of traditional music around the world. The exhibition and accompanying publication aim to represent rebetiko and its mythology through a contemporary visual outlook. How can a contemporary visual artist engage emotionally with and translate into image rebetiko music – ‘the songs of the wounded, the simple, pure, sensitive souls of Greece,’ according to Elias Petropoulos?

The exhibition features work by 50 artists, mostly contemporary ones. Marquee names, such as Tsarouchis, Tassos, Fassianos, who are admittedly to be expected in an exhibition of this kind, are of course represented. Yet foremost in our minds was to examine how contemporary art converses with rebetiko – how contemporary Greek artists approach and interpret it. For this reason, most works on view were specially commissioned for this exhibition. Looking at them, one can identify affinities, similarities, even leitmotifs, such as a chair (toppled, broken, transformed) – a recurring theme in many works. Although the artworks on view showcase a wide range of mediums, including photography, engraving, video, sound installation, performance, and artists’ books, pride of place is – justifiably – given to painting.

Rebetiko can be viewed through a contemporary art lens, in the same way that the British do it for their own musical heritage – rock and punk music. Notably, many international museums and art venues – from MCA Chicago, MACBA, and Kunsthalle Wien to the Barbican and ICA in London – have staged exhibitions exploring the relationship between rock music and the visual arts. Greek curators must approach the cultural heritage of their country with confidence. And rebetiko, case in point, is an important resource of the Greek cultural heritage. Considering that ‘Athens underground’ and ‘counterculture’ in Greece after 1980 have already been explored in art exhibitions, it’s time we looked at rebetiko, too, in the context of contemporary art.

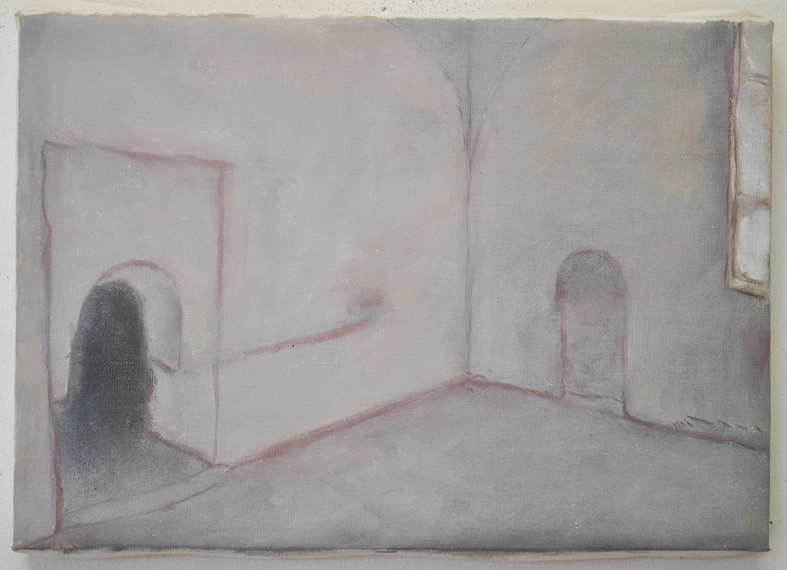

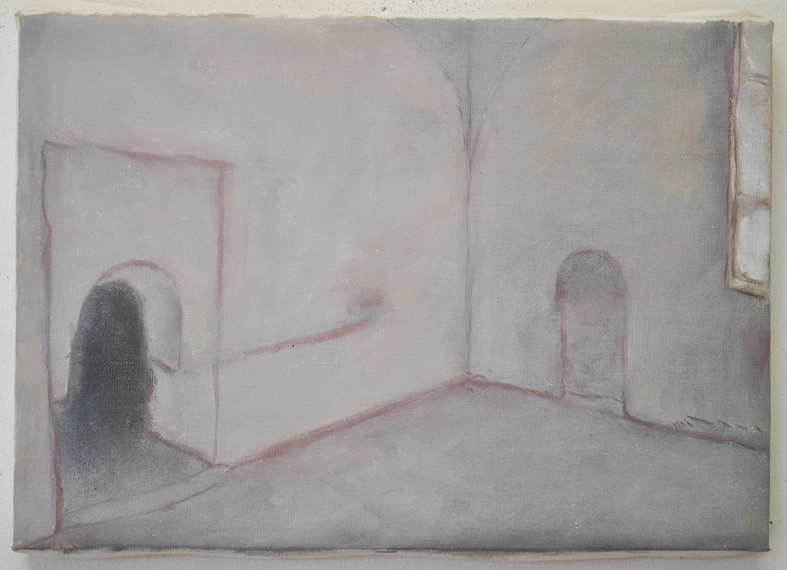

Ilias Papailiakis, Tsitsani’s Prison, 2017-2018, oil on canvas, 25×35,5 cm

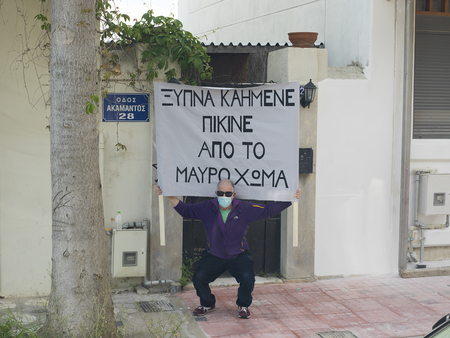

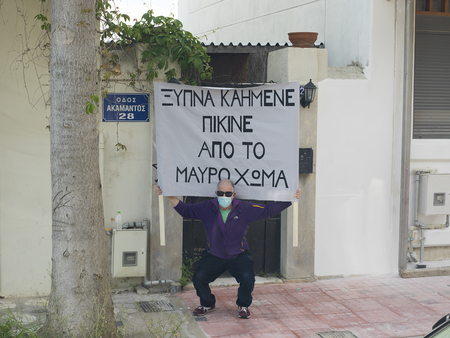

Yiannis Theodoropoulos, Αkamantos 28, Pikinos’ beer, 2021, inkjet print mounted on aluminum, 130×98 cm

Katerina Zacharopoulou, Rosa’s credenza, 2021 installation, video, objects and engraving, 210×120 cm

The impact of rebetiko seems to be particularly strong on younger generations. During the two lockdowns, numerous people – including many young persons – posted videos of rebetiko music on social media. In a difficult period, such as the one we have all been enduring for the last two years, these songs have served as a source of support. But it is in musical artists who are either also visual artists, such as The Callas, or flirt with the visual arts that this influence seems most apparent. Cases in point include Konstantinos Beta, Lena Kitsopoulou, Angelos Krallis (CHICKN), Negros tou Moria, Tasos Stamou. The appeal of rebetiko extends beyond the Greek borders. In his recent album Songs of Disenchantment – Music from the Greek Underground (2020), Brendan Perry, of Dead Can Dance fame, pays homage to rebetiko, showing how much this genre of music resonates with the artist. All these artists perceive rebetiko as rich, living heritage, as a vehicle they can use to create something new. Like the meme goes: REBETES NOT DEAD!

For many of the participating artists, this exhibition was an opportunity to explore their roots. For instance, the artwork by Yiannis Theodoropoulos is about Pikinos, a relative of the artist, who was stabbed to death in 1931 on Akamantos Street in Thiseio. Maria Tsagkari, on the other hand, researched the story of her great-grandfather, the acclaimed violinist Nikos Syrigos, better known as ‘Santorinios’. In her engraving, Rosa’s Credenza, Katerina Zacharopoulou trains her lens on Rosa Eskenazi, filtered through personal family stories and memories. This intimate relationship of artists with rebetiko is highlighted in the brief statement which each participating artist was invited to write for the bilingual exhibition catalogue. Similarly, visitors to the exhibition may find images and sounds that resonate with them for the same reasons – narratives related to their past, or present.

In addition to the art itself, there are two other notable aspects of this exhibition: Firstly, it features the enigmatic rebetiko artist Kostas Bezos (1905–1943), who signed his compositions as A. Kostis and was, in addition to music composer, a cartoonist. Excitingly, Bezos is featured in this exhibition with a series of cartoons from the Municipal Art Gallery collection. And secondly, in a seemingly simple yet highly symbolic curatorial gesture, a display showcases album covers and personal items belonging to Sotiria Bellou, shown side by side with photographs and personal items belonging to Maria Callas, which have been on view in the Olympia Theatre Foyer in recent years. These objects in the OPANDA collection can normally be viewed in the Melina Mercouri Cultural Centre’s permanent display. It’s a simple gesture, merely moving a vitrine from one location to another. But it brings together two towering figures of twentieth century music. Placing Bellou and Callas side by side illustrates a well-known statement by Yannis Tsarouchis: ‘I love Callas and Sotiria Bellou. And I don’t feel conflicted. Let those who are scandalised figure out why.’

To this day, when the words rebetiko and visual arts are mentioned in the same breath, the first things that come to mind may be Alekos Fassianos’s illustrations for books by Elias Petropoulos, Tassos’s engravings for Bellou’s album covers, or the zeibekiko dancers that were such a frequently represented subject in Tsarouchis’s paintings. Rebetiko intends to expand the visual representation of the world of rebetiko, fundamentally changing the way it is perceived in the visual arts. This exhibition is testament to the fact that rebetiko is not only of contemporary interest but also contemporary in form.