Yiannis Theodoropoulos

about

EXPERIENTIAL SCULPTURE

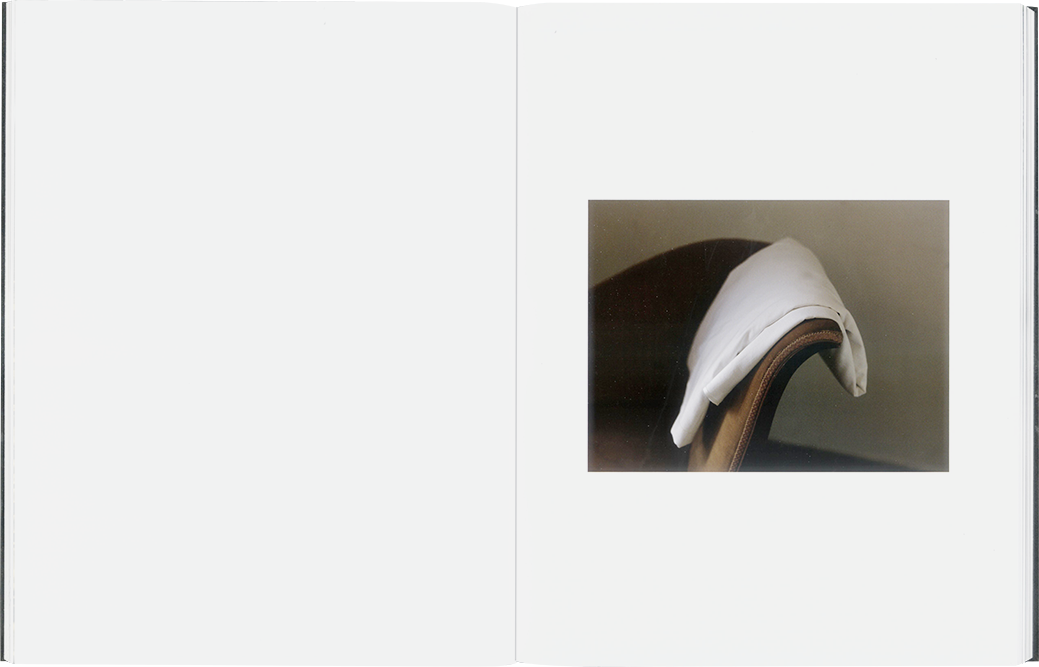

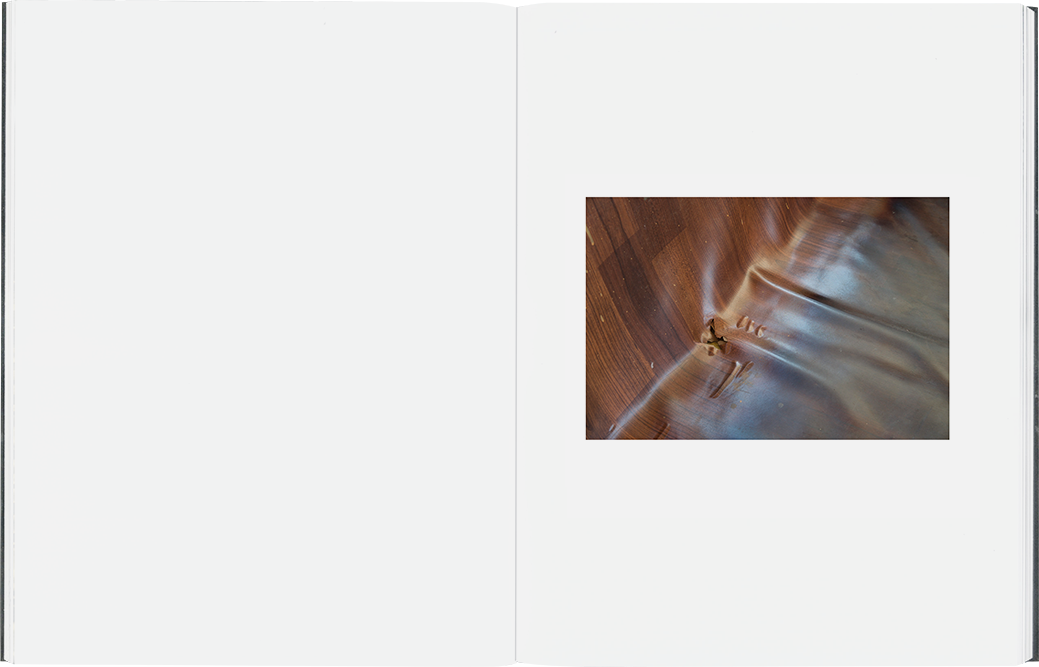

For the past 30 years I have been photographing objects and spaces that are usually inside my house in Mangoufana, but also in other places far from my home. I began by photographing interiors of greenhouses; their bright domes gave me the impression that I was standing inside a futuristic temple. Almost concurrently, I started photographing various structures, usually illegally built, that make up the modern Greek landscape at the outskirts of urban centres. Later, I started photographing inside my house, almost exclusively. I call that work experiential sculpture. By experiential I mean that the things I photograph are not random objects or landscapes that happened to lie before me, but things that are charged with a psychological, but also a physical, part of my every-day life. Essentially, they convey parts of my history, and so, I suggest, of our history; I emphasize this, meaning that they comprise a mosaic of aspects of modern Greek reality. It is not history recorded in linear fashion; I would say it resembles a psycho graph, like a mirror that reflects my internal life, with the “within” and the “outside” engaging in an on-going dialogue… Essentially I rediscover inside my house the landscapes outside, and outside I rediscover the landscapes that lie within me… We are our world (our home).

press

Hotel Splendid: A photography exhibition where the trivial becomes important

A Timeline of Silence

The work of Yiannis Theodoropoulos as seen by art historian/curator Christina Petrinou

publications

extras

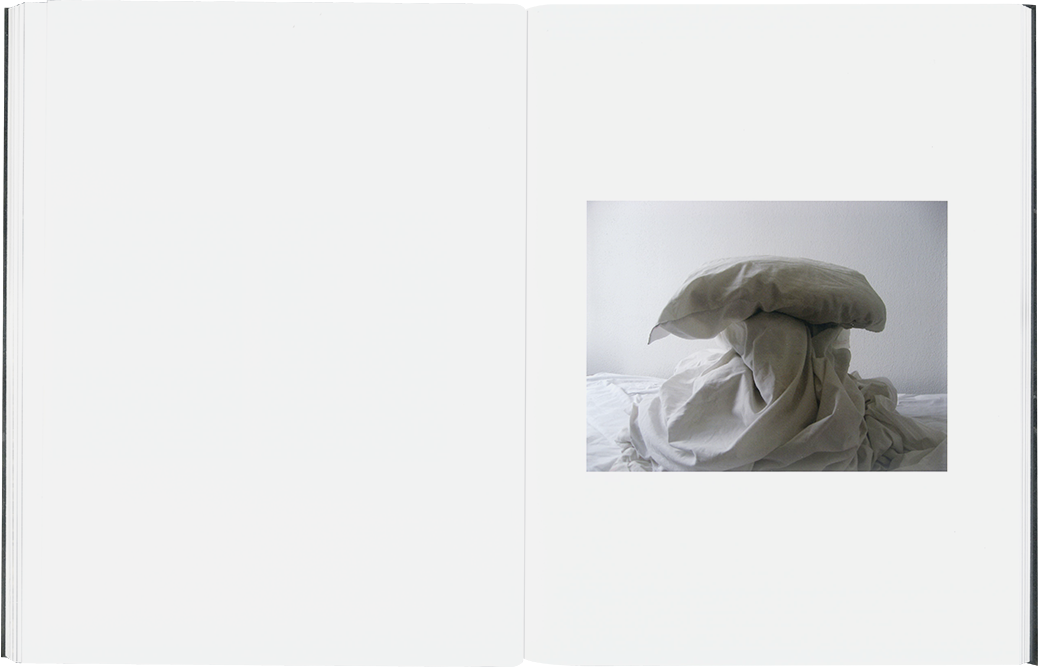

Topheth, Yiannis Theodoropoulos’s first book, is about the loneliness of objects, the memory of mosaic floors, the allure of bed sheets and of creases. It is also about the loss of love, the notion of sacrifice and (the process of) victimization, the search for a coherent subjectivity and the impossibility of this endeavour.

The principal theme of Theodoropoulos’s images is the “end of tradition”, as the artist himself notes; not just the tradition of photography obviously, but the end of a sense of commitment―personal, social, as well as artistic. From this perspective, Topheth marks the end of submission to perpetuating complexes that cause a slew of guilt and blame. His work encompasses Hölderlin’s insight in the poem Patmos (“But where there is danger, A rescuing element grows as well”) and Kafka’s response, so to speak, from The Blue Octavo Notebooks (“Hiding places there are innumerable, escape is only one, but possibilities of escape, again, are as many as hiding places”). The photographs included in Topheth are hiding places both for the artist himself and for the spectator who is ready to welcome them and grasp their peculiarity.

Topheth is a window into the interior world of a photographer who could also be a sculptor and who would like to to be a comedian. The key to reading Theodoropoulos’s works is the schizophrenic coexistence of the solemn and the ridiculous, the sacred and the profane, the depth of ancient Greek heritage and the lack of depth that characterises modern Greek culture.

Theodoropoulos’s home, where most of his images originate, is a crypt in all meanings of the word. It is a secret space, a place of worship, the house of a martyr who is being wrongfully persecuted by his fellow humans. What we are dealing with here is not a neutral space; hence the interiors or the “landscapes” that result from chronicling this house are not historical documents. He seems to be well aware of the fact that objects are often more enigmatic than stories. Remembering T. S. Eliot’s famous verse from The Waste Land, he can show us fear in a handful of dust. Similarly, through photographing a pile of potatoes or a piece of Feta cheese, he reveals to us the transcendental serenity of a “still life” and the enigmatic silence of objects. In the plethora of medicines and homeopathic remedies he makes known to us his faithful “companions”, while in a plastic black urn he converses with his father for the last time and reflects on the beyond (epekeina).

In Topheth, photographer Yiannis Theodoropoulos “strips himself bare.” The crypt opens up: his house in Magoufana―what the area of Pefki was once called―now resembles a museum of personal memories and illusive-destroyed collective dreams.

Edit: Christopher Marinos

Texts: Christopher Marinos and Yiannis Theodoropoulos

Design: Studio Lialios Vazoura